Ben Tibbetts Studio Home Services Archive Students About Contact Now Store Subscribe

Dreaming Up A Better Time Signature

January 19, 2013

Music notation did not appear suddenly in its current form; rather, it evolved over time until it reached its present incarnation. Presumably, it will continue to evolve as long as it is used. It's not perfect, and some relatively small changes might make it more intuitive. It would probably be good to make those changes, because more intuitive sheet music would likely be more conducive to high quality musical performances and coherent music theory.

Consider the time signature. This is what it looks like:

It is made of two numbers, one on top of the other. The top number indicates how many beats are contained in every measure. In every measure following this particular signature, the note values must add up to four beats.

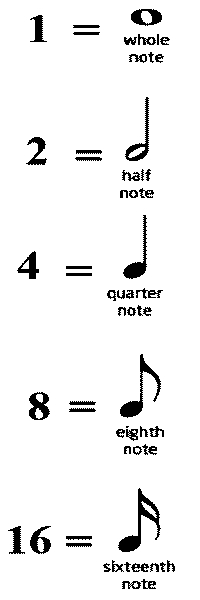

The bottom number indicates how long every note lasts using the beat as a unit of measurement. When the bottom number is four, that means that every quarter note lasts for one beat. When the bottom number is two, that means that every half note is one beat. When it's one, every whole note; when it's eight, every eighth note; when it's sixteen, every sixteenth note; and when it's thirty-two, every thirty-second note.

Although the bottom number determines the length of each note in terms of beats, the relationships between the notes stay the same. This is true no matter what the time signature is. For example, half notes are always twice as long as quarter notes; quarter notes are always twice as long as eighth notes; and eighth notes are always twice as long as sixteenth notes.

If I am writing music in 4/4, I could fill each measure with quarter notes. That would be correct...and also a little boring. There are many other correct options, such as four eighth notes and one half note; fourteen sixteenth notes and one eighth note; and a dotted half note and a quarter note.

If you feel lost at this point, you are not alone. I find time signatures counterintuitive and difficult to explain. When I was a kid, the bottom number in time signatures was described by one of my music teachers as showing "which note gets the beat". Later on, I asked for clarification, and I was told we would get to it later. Unfortunately, we didn't. Later on, I switched to another teacher, who assumed that I understood music fundamentals because I played piano at a relatively high level. For a long time afterwards the bottom number in time signatures remained mysterious to me.

Visually, I think part of the trouble with putting one number on top of another--like "4/4" or "6/8"--is that it is hard to infer what it might mean without someone explaining it. The bottom number is supposed to imply the following information:

Although this information is key to reading time signatures, it is totally unobvious.

There are also some traditions which cause pedagogical challenges. Time signatures are not interpreted the same way all the time. For example, 6/8 is supposed to imply that there are six beats in every meausure and every eighth note is worth one beat, but in practice the first and fourth beats of measures in 6/8 are usually accented. As a result, measures written in 6/8 sound like they contain two beats, not six.

Here is another example: the 3/4 time signature technically indicates that there are three beats in every measure and each quarter note is worth one beat. This is true a lot of the time, but not universally. Some fast music written in 3/4 stresses the first beat more than the other two, and as a result each measure sounds like it only contains one beat.

Time signatures could probably be made more self-explanatory by replacing the bottom number with whatever note value the composer wants to use to represent a single beat, like this:

In this image, the first time signature resembles 4/4 but the bottom number has been replaced with the image of a quarter note, which tells the musician that every measure is filled by the equivalent of four quarter notes. The second time signature resembles 2/2 but indicates that every measure is filled by the equivalent of two half notes. The third time signature resembles the traditional interpretation of a two-beat 6/8, but it does a better job of conveying that information by showing that every measure is filled with the equivalent of two dotted quarter notes. The fourth time signature resembles 3/4, and the fifth time signature resembles a nontraditional, six-beat 6/8.

This is only one example of a notational model that would probably work better than the traditional one. There may be better ways of communicating these concepts, and there may even be ways of experimentally determining optimal methods.

This is not a purely academic issue. I have worked with musicians who are confused about time signatures. Of the musicians I've met who do not read sheet music, several of them have said they were intimidated by the complexity of music notation. The challenge of learning to read music may be preventing talented people from entering the field. If that's true, who knows what music we may be missing out on? Of course, it is true that some musicians get by and even flourish professionally without reading music, but even those people's careers could potentially be improved by learning to read.

Ben Tibbetts Studio Home Services Archive Students About Contact Now Store Subscribe

Copyright © 2006-2023 Ben Tibbetts

change log